Written by Julius Meška

The 23rd of May 2023 marked a previously-unprecedented development in the Russian Invasion of Ukraine – Russian dissidents brought the war home.

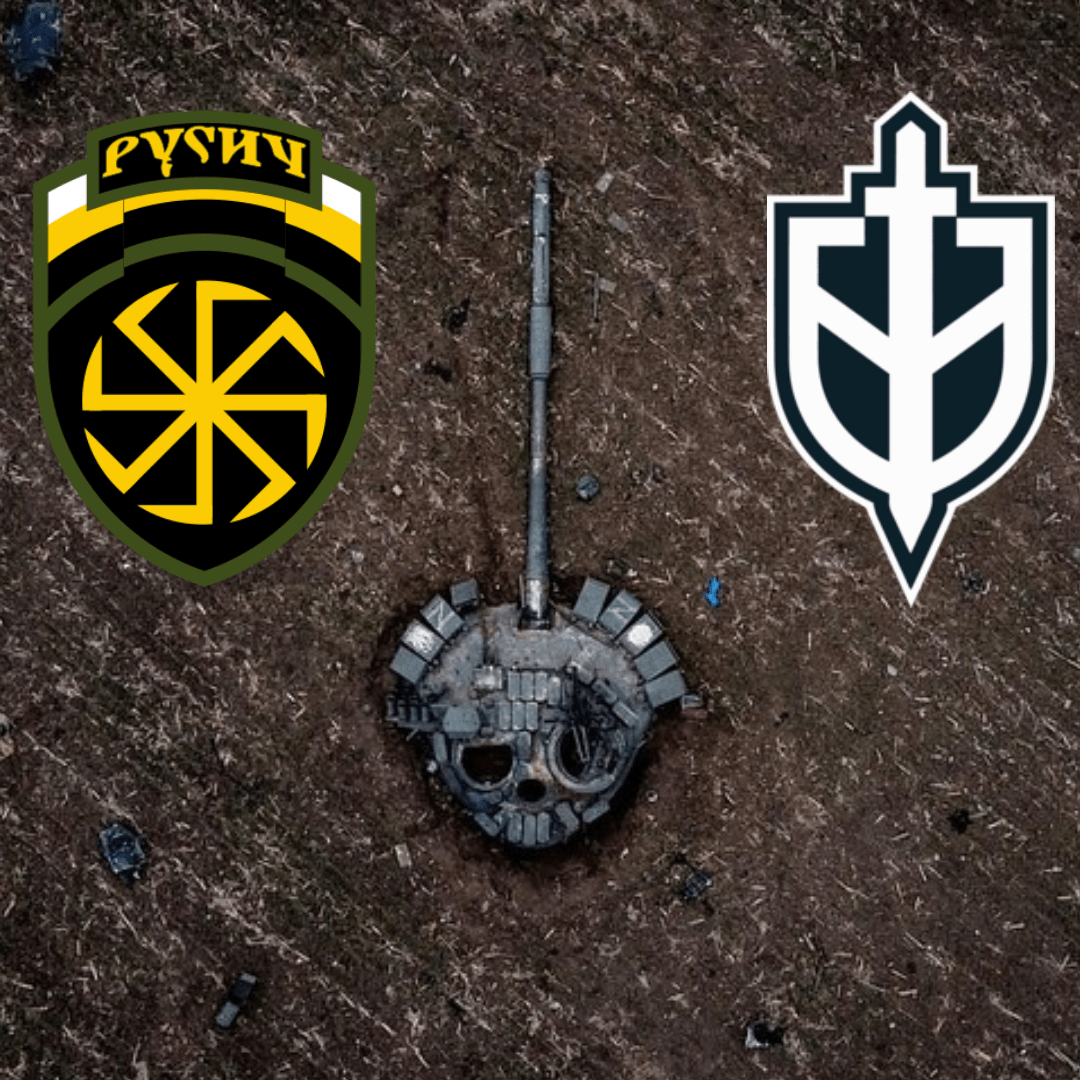

In the Russian border region of Belgorod, bordering northeastern Ukraine, two armed formations of the Russian opposition-in-exile carried out a raid, killing several border guards, and scoring a propaganda coup of photo-ops before retreating into Ukraine. The two formations were the ‘Freedom of Russia Legion’ and the ‘Russian Volunteer Corps’ (RVC), yet the latter stood out for a single reason – their ideology of Russian Neo-Nazism, led by bonafide reactionary-internationalist Denis ‘White Rex’ Nikitin.

Why were Russian ultranationalists engaged in violently opposing an imperial war launched by their autocratic state? Why were they not instead on the side of ultranationalists fighting for the Russian military, such as the ‘Rusich Group’? This article will briefly explore the genealogy of 21st Century Russian Neo-Nazism to its present division, deciphering the roots of its ideological divide, and what this reveals about ultranationalists when torn between loyalty to nation, and ideology. This will be driven by a comparative case study of the primary Russian Neo-Nazi paramilitaries and figures on both sides of the war – that of Denis Nikitin’s ‘Russian Volunteer Corps’, and Alexey Milchakov and Yan Petrovsky’s ‘Rusich Group’, before concluding on the key ideological similarities and differences between their respective conceptions of Russian Nationalism.

Russia for Russians – dissident origins of Russian Neo-Nazism

Since the unstable foundation of the modern-day Russian Federation, the principles of the Russian radical-nationalist opposition have rested chiefly upon opposition to Central Asian migration and the Putin government(s) – the latter for alleged inaction in the face of such migration, and for enshrining a model of citizenship that put ethnic Russians (Russkih) and non-ethnic Russian citizens (Rossiyani, such as Chechens and Tatars) on an equal basis. In these grievances, the Russian Neo-Nazi movement pre-2014 shared most of everything in common with neo-Nazi movements throughout the rest of Europe, and indeed was on friendly terms with similar movements in Ukraine and Belarus – as reported in Russian opposition outlet Meduza, “Russian nationalists regularly travelled to farright music festivals and concerts in Kyiv..and other Ukrainian cities. And Russian far-right bands often toured in Ukraine.”. Given that the Putin government criminalised and prosecuted such nationalism under political extremism laws, in the words of notable Russian nationalist Dmitry Demushkin, these neo-Nazis “traditionally hid from the Russian justice system in Western Ukraine..Ukrainian nationalists provided them all possible support.”.

This period of ultranationalist solidarity ended following the beginning of the Russo-Ukrainian Conflict in 2014, as Russian troops occupied Crimea, and subsequently supported separatist proxies in the Donbass region. The annual ‘Russian March’ of the united nationalist opposition experienced a split between those who, essentially, prioritised imperial expansion over domestic opposition, and those who stayed true to the dissident tradition over embracing Crimea’s “return to the Motherland”.

Today, this conflict between the ‘dissidents’ and the ‘imperialist’ neo-Nazis is fought in Ukraine – what drives them so apart as to spill the blood of those with the same nationalist conception of Russia, and more interestingly, what similarities remain despite it all?

The Russian neo-Nazism of the RVC

The ideology of the Russian Volunteer Corps is remarkably explicit – without even a full week having passed following the Belgorod Raid, it published a political manifesto titled ‘Homo Ethnicus’. It begins with a condemnation of the average apolitical Russian, their only concern being “the disruption of consumer goods supply chains” whilst “the Ukrainian population is under shelling and genocide” – a condemnation common throughout the wider anti-war infosphere generally – before moving onto establishing their own understanding of the previously-mentioned difference between Russkih and Rossiyanin; “passionate national forces versus pot-bellied philistines mired in everyday problems”. In this, the RVC establish themselves as a seeming vanguard of national purity, the last remaining ‘true’ ethnic Russians fighting for their conception of national liberation.

This is not a mere poetic interpretation, for the ‘Homo Ethnicus’, or ‘Ethnic Man, in question is the RVC’s reinvention of the Fascist ‘New Man’: the ‘Ethnic Man’ is one who internalises “ethnic (self)consciousness”, being “aware of their ethnicity..proud of it..and capable of ethnic solidarity”, becoming the “cornerstone of any long-term nation-state”. It is under the framework of this concept that the RVC outlines its priorities for Russia, being the creation of “a true nation-state, free from the Soviet past and from Liberal philistinism”, with the Ethnic Man being the positive inverse of the ‘Homo Economicus’, “whose only motive is materialistic interests”. By these principles, the RVC is not only fighting to support a broad pro-Ukrainian coalition alongside other Russian opposition forces – in the long-term, it is fighting to create a Russia under a completely new form of social organisation, an ethnic nation-state by and for “ethnically conscious” ethnic Russians.

Unlike the co-founders of Rusich, RVC leader Denis Nikitin’s portfolio of political activities prior to the war is much more international. From Switzerland to Ukraine, he founded and led a pan-European far-right Mixed-Martial Arts programme under his namesake, ‘White Rex’, before the war gave him the opportunity to turn peacetime martial training to wartime armed action. In an outdoor press conference following the RVC’s return from Belgorod, when asked if he does “mind being described as a neo-Nazi”, his reply was simple – “I don’t think its an insult”, before notably remarking on the “changed perception” of the media on “all those bad neo-Nazis” that were now fighting for Ukraine. Indeed, whilst nonchalantly honest on questions of ideology, RVC official communications continue to stress their fight for “freedom and justice” to the extent that the RVC’s existence is limited to its utility for Ukraine in the defence against Russia – one could only ponder how Niktin would reply to being asked of how it is like to fight for a Jewish president, as there has thus far been no mention of antisemitism in the RVC’s texts and communications.

The pro-Russian Nazism of Rusich

The Sabotage and Reconnaissance Group ‘Rusich’, simply shortened to the latter, does not have to face the RVC’s need for ‘optics’, or a good image in the media. Co-founded to support Russia’s proxies in Eastern Ukraine back in 2014, it gleefully joined Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022, counting “a number of people who belonged to Russian neo-Nazi groups in the 2000s”, with its symbol openly featuring the kolovrat (a ‘Slavic’ swastika variant used by such neopagans and neo-Nazis) in the fight against “Ukr-Bolshevist scum”. Despite one of the key aims of Russia’s invasion being the ‘denazification’ of Ukraine, the group has outwardly remained as true to its ideology as ever, to the extent that its official telegram channel posts veiled birthday wishes to Adolf Hitler every April.

In the words of its co-founder, Yan ‘Great Slav’ Petrovsky, “Rusich is a pan-Slavic, pan-Scandinavian group” who just as much “call ourselves Russian nationalists”. Unlike the RVC, it does not attempt to mask the antisemitism inherent within its ideology either, further justifying its fight against Ukraine as one against “the Khazar Khaganate, which is there again” – attempting to link a historically Jewish medieval polity that had controlled parts of 9th century Ukraine, to the modern Ukrainian state. The group’s other, more notorious co-founder, Alexey Milchakov, became infamous for stating in an interview “I am a Nazi..I say it directly: I’m a Nazi” – his notoriety stemming from his activity in Russian neo-Nazi groups in the 2000s, with a published text on how to abuse Ukrainian prisoners of war indicating a masochistic element to Rusich’s motivations that cherish the experience of war itself, with one member comparing the experience of wartime killing with that of “sexual desire”.

For most of the current War in Ukraine, Rusich has fought as a detachment of the mercenary ‘Wagner Group’, having supported its leader Evgeny Prigozhin’s rejection of “denazification” as a rationale for the invasion of Ukraine, and instead itself claiming that it is fighting “to avenge Donbas, for living space, and for combat experience”. It is this association with the Wagner Group, that brings us to a key observation of the ideological link between Rusich, and the RVC.

Summary

The presence of the Russian neo-Nazis of the Russian Volunteer Corps, and the Rusich Group, respectively, reflects a divide within 21st century Russian radical nationalism. This is between those who, on the one hand, embody a tendency of reactionary internationalism and prioritisation of the domestic political struggle over that of the nation’s external struggles, and on the other, those who prioritise the defence of the nation’s imperial status over political purity at home. Curiously, it is Rusich that has been most open about its ideology, despite fighting in a war waged for ‘denazification’, justifying the war in its own terms as one against a Jewish-led government for the imperial interests of the nation. However, whilst the RVC attempts to avoid the topic of its ideology whilst stressing the fight for ‘freedom and justice’, it refuses to hide it when questioned either.

Whilst the RVC may pale with Rusich regarding its enthusiasm for violence, most crucially, the ideological link between Rusich and the RVC remains. Following the Wagner Group’s failed overthrow of the Russian military establishment and Prigozhin’s death, the RVC expressed sympathy for Wagner’s “March of Justice” and called for its now-disgruntled remaining fighters – many of them undoubtedly war criminals – to join its ranks. With this in mind – once the war is over, will there be anything to divide the neo-Nazis on both sides of the front, bar the blood shed thus far?

To date, there have been no confirmed instances of direct combat between the RVC and Rusich. The RVC remain far smaller and less active than their pro-war contemporaries, their activity largely composed of small cross-border raids, and online propaganda.

Whilst no entity but Ukraine itself has the right to control the means by which it resists its genocide, one must consider the likely consequences of legitimising a group such as the RVC as a visible pillar of anti-Putinist resistance – in no possible circumstance should Nazism find itself on the winning side in Europe.

Bibliography

Homo ethnicus / Человек этнический – Telegraph

Dying to kill The Russian neo-Nazis fighting Vladimir Putin’s war to ‘denazify’ Ukraine — Meduza

How Donetsk Militias Split the Russian March: Society: Russia: Lenta.ru

Russian GRU spetsnaz soldier Milchakov, openly admitted he was a Nazi in a TV interview

Meet the Russians fighting their fellow countrypeople as the Ukraine war rages on | ITV News