Written By Jude Al Issa

Prior to 2015, modernity was neither welcomed nor believed to have an audience in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. For pious tribal people, camera phones in the early 2000s were an unnecessary luxury, cinemas considered as the works of the devil, and religion was a public activity that must be imposed by the Commission for the Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice. However, Max Steineke’s discovery of an exaggerated amount of oil in Dammam’s oil well number 7 in 1938 forced rapid globalisation and modernisation in a small area in Saudi Arabia.

Concessions on the application of tradition and religion were made to an exclusively welcomed people within a small enclave in the Eastern Province, the Saudi American Aramco Camp in Dhahran. Through a literal spatial division, rights are reshuffled and prescribed on merits based on the role in transferring the Kingdom’s land yields into the sovereign wealth fund. An expatriate from America held untouchable elite status, while the weakly educated national was fortunate only because of his primordial links to the rich land. A neo-colonial racial element brought by the United States of America is a prominent feature in the identities created within the enclave, which influenced a tendency towards a bottom-up resource nationalism amongst Aramcoians (Koch and Perreault, 2019). An inversion of identity roles in Aramco becomes successful around the 1970s by adding a third group in the racial hierarchical pyramid, South Asians, to occupy the base instead of the nationals. Like a credit system, the greater the work, the more the rights. However, access to rights within and the concessions made for the camp illuminate the contradictions in space and time reflective of changing state-society relations. The contradictions paved the way for a cultural resistance between the fundamentals outside the gates influenced by Islamism and supported by the aforementioned Commission and the ‘moderates’ within who either heard the echoes of their voices in Arab nationalism or abstained from engagement outside the Aramco camp.

‘Little America’ in Dhahran

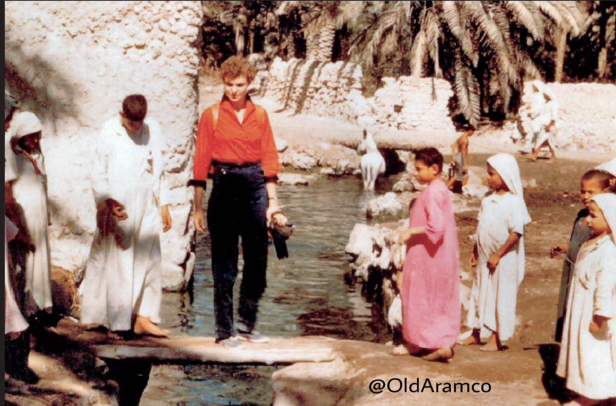

Best described as ‘Little America’ (Nehme 1994, 930), the Saudi American Aramco Camp represents a Houston settlement to house expatriates in an environment more familiar. The significance of the space that the camp occupies how it juxtaposes its surroundings.

Imagine an oasis that not only feeds drought and shades from the sun but also feeds a taste of American freedom and shades from the Commission for the Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice’s oppression. Heavy surveillance, security and massive walls shelter both expatriate camp life and the parts of Saudi culture influenced by Islamism from glimpsing an ‘other’. Standing outside the gates, you can see the trees, the greenery of the hills of the Dhahran and the whiteness of its majority population cannot go unnoticed. From the inside the camp, you cannot see the outside as it is just a flat desert. When you are inside, there is not an outside.

The space contributed to the attractiveness of Little America, which to some fundamentalists was equated to a devilish desire to deviate away from Islam. The juxtaposition depicts the contradictions within the Saudi identity since the establishment of the state, between the religious fundamentalists and modernised, urban Saudi Arabians fearful of being subjected to cultural consequences empowered by the Commission. Within the fault line emerges a political identity confronting the Saudi Arabian monarchy for the first time, the Free Princes Movement. The movement aligned with Gamal Abdel Nasser’s Pan-Arabism and was supported by Abdullah Tariki, co-founder of OPEC and the first Saudi Oil Minister (AlQash’ami, 2015). Another identity strain is that of a quietist national immersed in Aramcoian enjoyments of life, freedom, and career opportunities. Then, the racial divisions are reminded of when one realises drinking water is segregated between bottled water for employers and tap water for employees (AlNoaimi, 2016). The national could not become an employer at the time, one neo-colonial feature that AlNoaimi criticised. This critique develops from criticism of the American treatment to eventual nationalist sentiments that call for the Saudification of Aramco.

Aramco’s exclusion from Saudi Arabian society, an enclave of modernisation that polarises the population, carried colonial legacies to create a miniature nation. Besides the identity illustrated with a flag and dialect, its racial labour divisions have created Aramco exclusive rights distributed in order of priority to expatriates -Western citizens-, nationals -Aramcoian Saudi Arabians- and foreign workers -South Asians and non-Aramcoians-. The differences will be highlighted by delving into the characterisations of the Aramcoians.

‘Aramcoians’

The name Aramcoians is reused from a journal written by Saudi Arabian students on Aramco scholarships (AlMaghlouth, 2000). They speak about their unique experience as the first to be sent to study in East Asia, learn the languages and immerse themselves in their culture. As they describe, they are unlike others who study abroad too close to home in Egypt and Lebanon. They travelled further, saw more and were different and better. They feel a sense of superiority in their privilege to be distinguished from the educated -or not educated- in Saudi Arabia. In their story, there are two characteristics of the Aramcoian. First, as international scholars, they are more intelligent and second, they possess a strong primordial loyalty to Aramco that is inseparable from oil. Education’s strong links to the Aramcoian identity are attributed to Aramco’s historical role in creating and promoting education for the new Saudi Arabian state to support an increasing need for national workers in Saudi Aramco to continue extracting oil.

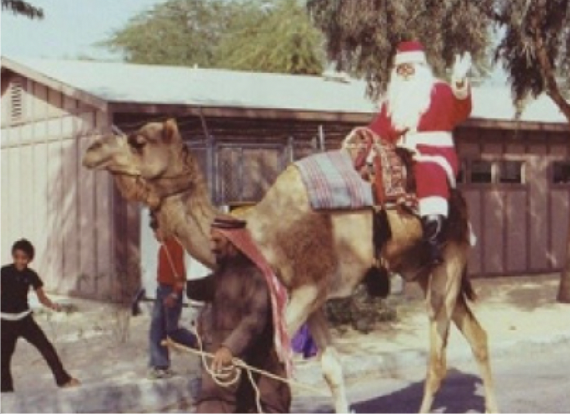

I attempt to hunt for the Aramcoian identity as a critical analysis of hints of bottom-up nationalism restricted within literal gates in the governorate of Dhahran, Eastern Saudi Arabia. To the local reader, the identity is recognised through English proficiency, high levels of education and a more controversial liberal way of life. Against this surface-level perception, the Aramcoian identity possesses a primordial entitlement to the oil wealth, a sense of superiority for being better educated, and a sense of mimicry to an American lifestyle celebrated through Christmas and Halloween in Little America to visibly display religious moderation, escaping the overarching Saudi Arabian outside the Aramco gates.

The Aramcoian identity is a combination of a primordial entitlement to oil, whose extreme form prescribes the right to oil and its rich yields to the Arabs who have embraced the desert above the oil rigs as a homeland. ‘Arab oil is for Arabs’, as Abdullah Tariki expressed with nationalist sentiments that led to his eventual dismissal from OPEC, the ministry and the Aramco board (AlSaif, 2012). Specific to this version of nationalism is its characterisation as resource nationalism that occurs from the bottom up without state influence. On the one hand, it resents the ‘white’ power that unapologetically claims oil, punishing the white superiority and entitlement in the 1970s by blocking exports to protect the Arab pride after defeat in the 1967 Palestinian-Israeli war. On the other hand, it continues the Jim Crow legacy of neglect and exploitation of the South Asian labourers who sought an opportunity for life in Saudi Aramco (Wills, 2019). A less extreme expression of the Aramcoian identity is in its adoption, or even pioneering, of a moderate and private Islam in Eastern Saudi Arabia. On either end of the spectrum, this identity is nourished through firstly a prominent and visible spatial division of Aramco camp in Dhahran from the rest of Saudi Arabia and then a corporate nationalisation of the resource and the company, transforming it from an American Aramco to a Saudi Aramco.

While Aramco continues to generate the overwhelming majority of the Kingdom’s sovereign wealth and the future of generations to keep the machine working, life within Aramco’s walls brings nationals closer to elite expats and further from inferior migrant workers. Within the space that counters tradition outside of its gates is a phenomenon that, in the most pessimistic terms, can be described as a settlement and, in the more moderate sense, perhaps a concession within Saudi Arabia’s state theory that allows foreigners an American freedom to support the sovereign wealth fund. In either case, the contradictions adapted their approach within the camp to continue the American ideal of freedom, positioning themselves within the camp above Saudi Arabia and acknowledging the interdependency within resource nationalism on a producer and consumer.

Bibliography

AlKinani, Mohammed. Retired Aramco staff recall Christmas festivities in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province | arab news, December 26, 2020. https://www.arabnews.com/node/1782916/saudi-arabia.

AlMaghlouth, Abdullah Ahmad. أرامكويون من نهر الهان إلى سهول لومبارديا. AlObeikan: Khobar, 2020.

AlNoaimi, Ali Ibrahim. من البادية الى عالم النفط. The Arab Dar for Science, 2016.

AlQash’ami, Mohammed bin Abdulrazzaq. عبدالله الطريقي مؤسس الأوبك والممهد لسعودة أرامكو. Arab Publishing Foundation, 2015.

AlSaif, Mohammed Abdullah. عبدالله الطريقي صخور النفط ورمال السياسة. Jadawel, 2012.

Koch, Natalie, and Tom Perreault. “Resource Nationalism.” Progress in Human Geography 43, no. 4 (June 18, 2019): 611–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132518781497.

Nehme, Michel G. “Saudi Arabia 1950–80: Between Nationalism and Religion.” Middle Eastern Studies 30, no. 4 (October 1994): 930–43.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00263209408701030.

Wills, Matthew. “The Jim Crow Roots of the U.S.-Saudi Arabia Relationship – Jstor Daily.” JSTOR Daily, September 27, 2019. https://daily.jstor.org/the-jim-crow-roots-of-the-u-s-saudi-arabia-relationship/.