By Layla Al Dabel

Longing, affection, and sentimentality for the past. Nostalgia comes from Greek nostos (return home) and algos (pain) (1). Originally described as a medical condition of homesickness, nostalgia today represents a sentimental yearning for an idealized past (2). For nationalist movements worldwide, this emotional longing isn’t just incidental – it’s a fundamental rhetorical strategy that transforms political ideologies into visceral, personal experiences.

Donald Trump’s ‘Make America Great Again’ (MAGA) emerged as the quintessential example of nostalgic nationalism in contemporary politics (3). Popularized during his 2016 presidential campaign, the slogan quickly transcended mere political messaging to become a powerful symbol of nationalist identity and belonging for many Americans. Its power lies in a three-part narrative that guides all effective nationalist nostalgia: America was once great; it has declined or been lost; and finally, it must be restored – with Trump positioned as the sole agent of this restoration (3).

What makes MAGA particularly effective is its strategic ambiguity (4). The slogan never specifies when America was great – allowing different constituencies to project their own idealized past onto the phrase. For many white working-class Americans, it evokes the economic stability of the 1950s-60s, when manufacturing jobs provided middle-class lifestyles with single incomes (5). For Christian conservatives, it suggests an era when religion and traditional values dominated public life (6). For older conservatives, the reference point might be Reagan’s 1980s, defined by patriotism and American global dominance (7). This ambiguity reveals nostalgia’s core function in nationalist rhetoric: creating what Benedict Anderson called an ‘imagined community’ (8). MAGA does not simply propose policy – it constructs a mythic shared past that binds supporters into a cohesive identity. Wearing a red MAGA hat became more than merchandise; it transformed into a uniform declaring membership in this imagined community of ‘real Americans’ seeking restoration (9).

The narrative of decline is equally crucial to nostalgic nationalism. MAGA’s emotional potency stems from its framing of present America as fallen from grace. This creates both urgency and an implicit set of enemies – those supposedly responsible for the decline. Without explicitly naming them, the rhetoric identifies scapegoats: elites, immigrants, globalists, progressives (6). In this way, nostalgic nationalism defines belonging not just through shared positive memories but through shared resentments. We see similar patterns in other nationalist movements. Brexit’s ‘Take Back Control’ slogan echoed MAGA’s structure: Britain had sovereignty (past greatness); the EU took it away (decline); Brexit would restore it (redemption) (10). Both movements deployed nostalgia to simplify complex historical and economic realities into emotional narratives of loss and potential recovery.

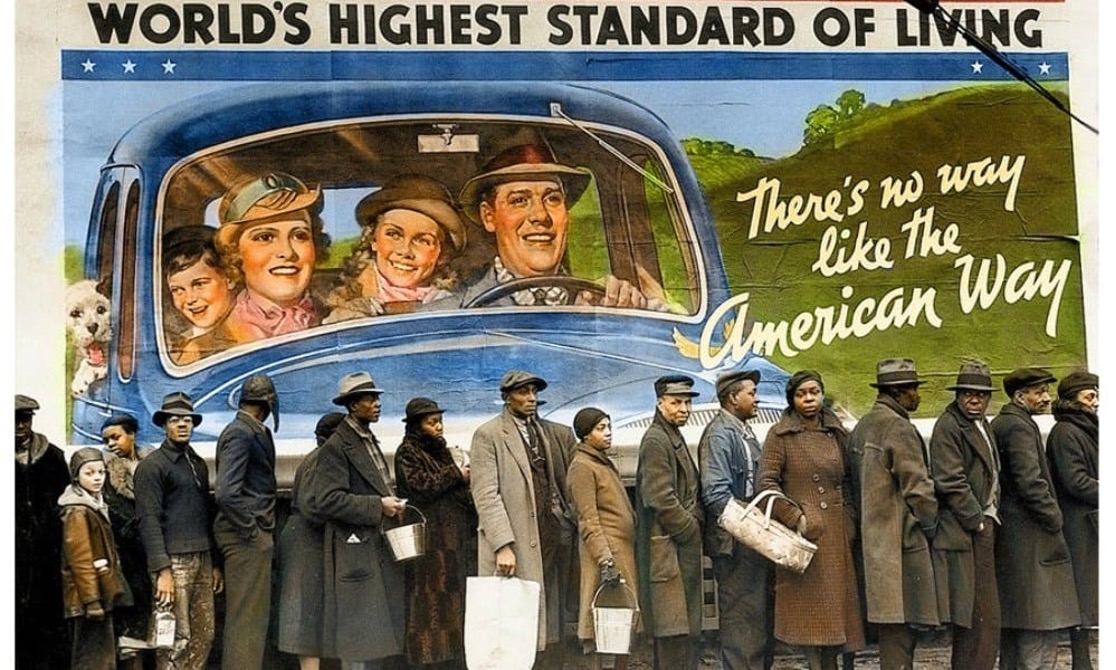

Why does nostalgic nationalism work so effectively? It offers emotional simplicity in times of bewildering change. It unifies disparate groups under a shared feeling of – we had it better (4). It creates clear villains responsible for national decline. Perhaps most importantly, it allows people to express anxiety about the present without appearing reactionary – they are not opposing progress, they’re ‘restoring greatness.’ However, this rhetoric carries significant dangers. It flattens history, erasing its complexities and contradictions. The 1950s economic prosperity MAGA often evokes coincided with racial segregation and limited opportunities for women and minorities (10). Nostalgic nationalism selectively remembers what benefits the dominant group while strategically forgetting what does not. It excludes those whose experiences do not match the mythologized past – for whom America was never ‘great’ to begin with (10).

Ultimately, nationalist nostalgia is not about actually returning to the past. It is about using selective memory to reshape who belongs in the present – and who does not. By understanding how movements like MAGA deploy nostalgia, we gain crucial insight into how identity becomes politicized, how belonging is defined, and how the past is continuously reinvented to serve the power struggles of the present.

References:

Cover Image (https://www.deviantart.com/keldbach/art/There-s-No-Way-Like-the-American-Way-865910324)

- Boym, S. (n.d.) Nostalgia. In: Atlas of Transformation. Available at: http://monumenttotransformation.org/atlas-of-transformation/html/n/nostalgia/nostalgia-svetlana-boym.html (Accessed: 5 April 2025).

- Fuentenebro de Diego, F. and Valiente Ots, C. (2014) ‘Nostalgia: a conceptual history’, History of Psychiatry, 25(4), pp. 404–411. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0957154X14545290.

- Behler, A.M.C., Cairo, A., Green, J.D., and Hall, C. (2021) ‘Making America Great Again? National Nostalgia’s Effect on Outgroup Perceptions’, Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 555667. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.555667.

- Youngblood, M. (2020) Why Political Ambiguity Appeals to the Masses. SAPIENS. Available at: https://www.sapiens.org/culture/shetkari-sanghatana-donald-trump/ (Accessed: 5 April 2025).

- Rose, S. (2017). ‘Manufacturing and the Economic Position of Men without College Degrees’. Urban Institute. Available at:https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/97786/manufacturing_and_the_economic_position_of_men_without_a_college_degree.pdf(Accessed: 5 April 2025).

- Perry, S.L. (2021). ‘The “Right” History: Religion, Race, and Nostalgic Stories of Christian America’. Religions, 12(2), 95. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12020095 (Accessed: 5 April 2025).

- Schmitz, A. (2012). ‘Chapter 13: The Reagan and Bush Years, 1980–1992’. In: United States History, Volume 2. Available at: https://2012books.lardbucket.org/books/united-states-history-volume-2/s16-the-reagan-and-bush-years-1980.html (Accessed: 5 April 2025).

- Anderson, B. (1991). Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Rev. edn. London: Verso. ISBN 9780805271775.

- Endom, B. (2021). ‘A Hat that Trumps Personal Identity’. REMAKE, Issue 2. Available at: https://remake.wustl.edu/issue2/endom-a-hat-that-trumps-personal-identity (Accessed: 5 April 2025).

Elgenius, G. and Rydgren, J. (2022). ‘Nationalism and the Politics of Nostalgia’. Sociological Forum, 37(S1), pp. 1230–1243. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/socf.12836