By Madeleine Pearson-Gee, Theodore Browning

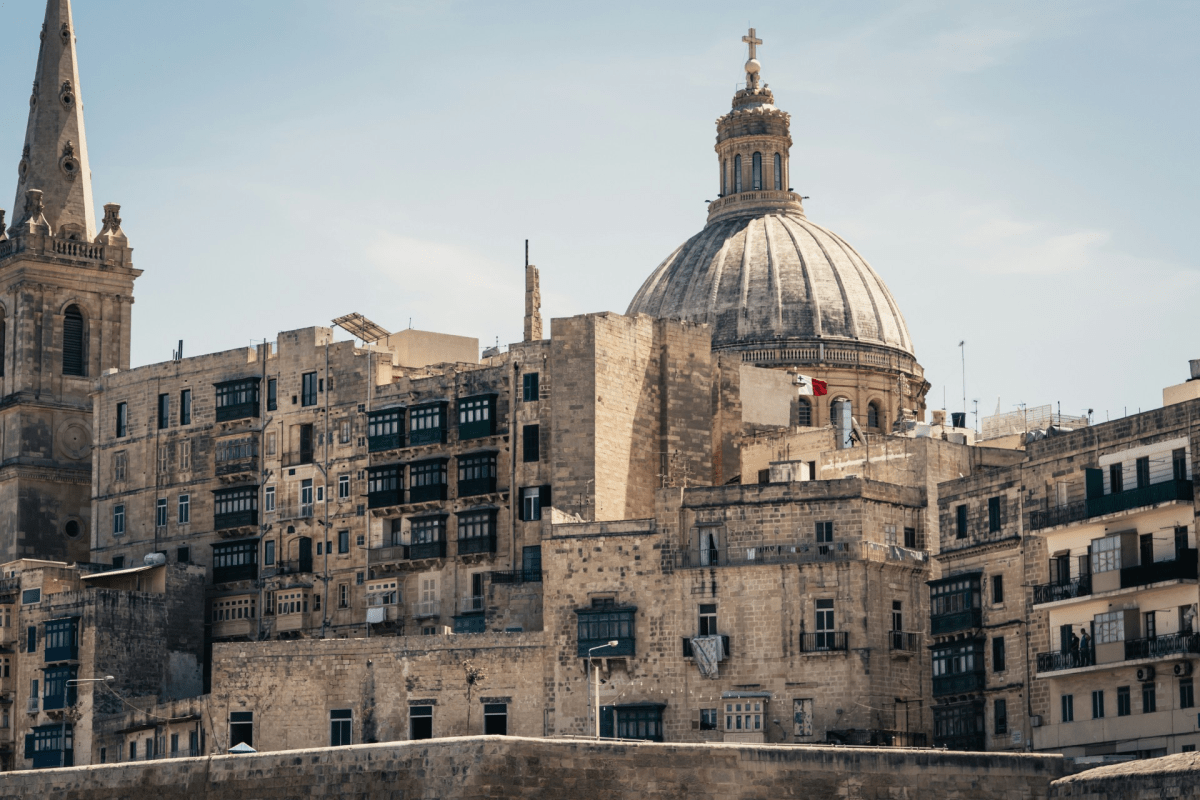

The island nation of Malta has a greater concentration of churches than any other non-Vatican country in Europe. Church-going participants in Malta’s booming tourism economy, however, are often taken aback when the Maltese mass first mentions God – the priest’s words are l-imħabba ta ‘Alla. ‘Alla’ is a word of Arabic origin, and sounds distinctly Islamic to most Christian ears. They would however be ill-advised to mention this to their local co-congregationalists: the Maltese national identity claims a historic affinity with Mediterranean and specifically Italianate culture, and an aversion to what they perceive as an invasive Saracen antagonist. This unique discordance between the nation’s history and its imagined identity, coded into the character of its language, challenges the traditional relationship between language and nationality assumed by generations of nationalist theory.

The history of the Maltese ‘language question’ is a vexed ménage à trois. Henry Frendo describes a limited ‘triglossia’, with an early modern Italian-Maltese bilingualism giving way to a colonial English-Maltese successor, with a contracted period of overlap and struggle. The Maltese language itself resembles a bastard child of Maghrebi Arabic and Sicilian; it’s a unique hybrid language in which Semitic and Indo-European elements have been deeply intertwined over several centuries. This reflects Malta’s fate as a geopolitical bellwether in the Mediterranean, continuously swept up in power dynamics, at various times Roman, Aghlabid Arab, Norman, Aragonese, Hospitaller, French, and British. Amongst all this, Italian had emerged as the dominant language of the Maltese literati by the sixteenth century, but with Maltese still the primary vernacular of the countryside and working classes. It was in the context of this Italian encroachment on Maltese society that Mikiel Anton Vassalli emerged as the champion of the Maltese language, rallying against the barbarizzare l’idoma nativo (barbarisation of the native idiom) under pressure of the Mediterranean lingua franca. Building on Vassalli’s efforts, Maltese began to grow as a symbol of national identity throughout the nineteenth century, working in tandem with the growing Maltese ethnic awareness under both Napoleonic and British colonial rule. Many early anti-British nationalists, however, insisted on their connection to Italy, even proclaiming Malta as essentially Italian – not just linguistically but nationally. Enrico Mizzi, decades-long leader of the Maltese Nationalist Party, declared in 1916 that the island’s nationality was ‘neither English, nor African, but simply and uniquely Italian.’ The attempted introduction of English by the colonial government faced another challenge: the Maltese people, committed to their Mediterranean identity, struggled to accept speaking a northern, Germanic tongue. Much of the historical Maltese struggle to define their linguistic identity was not so much about who they wanted to be as who they didn’t want to be: not Anglo-Saxon, and certainly not Arabian.

Language has long been treated as a defining feature of national identity, either as a point of reference such as in Germany, or a homogenising instrument as in France. But Malta and Maltese don’t fit neatly into this perspective. The Maltese language represents not a historical continuity, as is claimed for example by German linguistic nationalists, but reflects a long history of conflict and interplay between different identities and their associated tongues. Moreover, Maltese did not eventually emerge as the dominant literary language of the island. The Times of Malta, an English-language newspaper, still has the widest circulation of any newspaper in the country. While Maltese has become the primary language used in government, English is more prevalent in university education and as such plays a key role in the development of politicians’ literary consciousness. Unlike in Germany or Italy, where literary languages over time encouraged national linguistic coalescence around great authors such as Goethe or Dante, most of the historical corpus of Maltese literature is written in Italian.

So what is the answer to the language question? In 2016, Marc Scicluna in the Times of Malta wrote that ‘today’s language question is… about standards of both spoken and written English’. Scicluna rallies against the treatment of English instruction as teaching a foreign language, and instead champions ‘Malta’s unique selling point as a country which uses English as one of its official languages.’ What emerges from perspectives such as his is a relationship with language that is fiercely pragmatic. Malta has other, more powerful markers of shared identity—Catholicism chief amongst them—and so needs not treat English and Maltese as enemies in a modern linguistic battle. Instead they are allies, and the nation’s natural bilingualism sets its people in good stead.

Bibliography

Cassar, Carmel, ‘Malta: Language, Literacy and Identity in a Mediterranean Island Society’, National Identities, Vol. 3, No. 3 (2001), pp. 257-275.

Frendo, Henry, ‘Language and Nationality in an Island Colony: Malta’, Canadian Review of Studies in Nationalism, Vol. 3, No. 1 (1975).

Frendo, Henry, Language and Nationhood in the Maltese Experience (Malta, 1992).

Grima, Antoinette Camilleri, ‘The Maltese Bilingual Classroom: A Microcosm of Local Society’, Mediterranean Journal of Education Studies, Vol. 6, No. 1 (2000), pp. 3-12.

Gullick, C. J. M. R., ‘Language and sentiment in Malta’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, Vol. 3, Nos. 1-2 (1974), pp. 92-103.

Lucas, Christopher and Čéplö, Slavomír, ‘Ch. 13: Maltese’ in Christopher Lucas and Stefano Manfredi (eds.), Arabic and contact-induced change (Berlin, 2020), pp. 265-302.

Sciberras, Paul, ‘The Tradition of Religious Translations in Malta’, Melita Theologica, Vol. 68, No. 1 (2018), pp. 45-63.

Sciriha, Lydia, ‘The Rise of Maltese in Malta: Social and Educational Perspectives’, Intercultural Communication Studies, Vol. 11, No. 3 (2002), pp. 95-106.