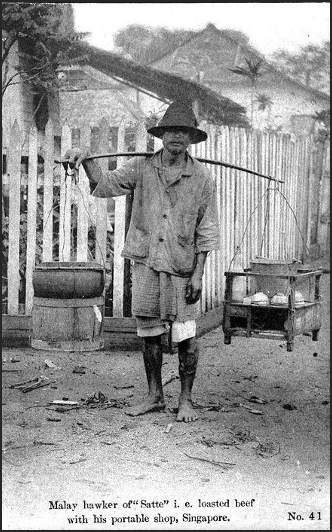

The history of hawker culture in three images taken in 1907, 1965, and c.1980 respectively: Source: Roots.Gov.SG

By Jing Kai Lee and Ashley Tan

The story that often comes to mind in discussions of Singapore today is its economic miracle—an outpost founded by the East India Company in 1819, moving from Third World to First within a single generation after independence in 1965. Quite literally fuelling this rise, however, was Singapore’s hawker culture, which flourished in parallel to Singapore’s transformation and sustained the workers who built modern Singapore.

Hawker culture in Singapore emerged spontaneously in the 1800s, when immigrants turned to street hawking as an affordable and accessible means of entrepreneurship. Selling food from mobile stalls, they moved through the streets and filled them with life, colour, and aromatic whiffs of freshly cooked meats, soups, and sweets. By the 1960s, hawker culture began to take on a more institutionalised form. The newly independent Singaporean government, aiming to rebrand Singapore as a business hub, sought ways to clean and order its streets. This eventually led mobile street hawkers to relocate into open-air physical complexes—what we now know as hawker centres.

Source: Guardian. Chinatown Complex. An example of a hawker centre today.

Today, hawker centres are widely recognised as an indispensable part of Singapore’s national identity, with 9 out of 10 Singaporeans considering them so. What makes hawker culture so central to the Singaporean national identity? We argue that beyond representing a common Singaporean passion for food, it also embodies the convergence of two strands of Singaporean civic nationalism: a flat, multiracial identity and an identity shaped by the value of excellence.

A flat, multiracial identity is fostered with hawker centres acting as a common space where different racial subcultures converge through food. Singapore’s common spaces policy fosters national cohesion by creating shared environments where people from diverse racial backgrounds interact, cultivating social understanding through shared experiences. In contrast to London’s food halls, which are far pricier and less ubiquitous, dining in hawker centres is an affordable, everyday routine, with many Singaporeans having one within walking distance of their home. It is this unique blend of multiculturalism, affordability, and accessibility that makes hawker centres highly frequented common spaces in Singapore, resulting not only in occasional cross-racial engagement but also in everyday interactions that blur racial boundaries themselves. More broadly, hawker centres should be seen as one of many elements in Singapore’s wider common spaces strategy, which also includes Housing Development Board precincts (interracial public housing) and racially-integrated national schools to cultivate a flat multicultural identity rather than one premised on identitarian hierarchy.

Moreover, while Singaporean exceptionalism is often associated with its economic success, its underlying ethos of excellence is arguably evident in the hawker trade, where generations have dedicated themselves to perfecting their craft. For example, satay store owner Ms Seow Lai Hao, who often serves long queues of customers, shared the experience of having no customers when she first started. In her recollection, ‘it took a lot of trial and error’ to get cooking techniques ‘just right’. A striking number of hawkers have also earned recognition in the Michelin Guide—an achievement that, given Singapore’s small size and the guide’s usual focus on high-end dining, reinforces the broader national aspiration of punching above its weight. Hawker culture therefore embodies Singaporean excellence: everyday Singaporeans who, through grit and dedication, have turned humble food into a national treasure and global icon.

Hawker culture has hence become an important means of identity-making for Singaporean nationalism, defining one facet of Singaporean-ness as a passion for food, participation in common spaces, and holding shared Singaporean values. This form of civic nationalism is not just pluralistic but also highly inclusive. For one, it allows new citizens who appreciate and regularly engage in hawker culture to more readily identify as Singaporean and be accepted as such. In other words, they are afforded significant agency in determining their identity through practices and habits, rather than being constrained by birth statuses. The insider-outsider divide is also less rigid, as engagement with hawker culture exists on a spectrum rather than as a fixed binary. Furthermore, hawker culture does not imply a clear normative identitarian hierarchy, as it promotes pluralism rather than imposing culinary assimilation.

Looking forward, hawker culture faces challenges to its future. Far fewer young Singaporeans today are keen to take up the hawking trade, given its long hours and tight economics. Rising raw materials and staffing costs have also put increasing pressure on hawker food’s affordability. These dynamics cast uncertainty over hawker culture’s future and its role in Singaporean nationalism as a common space and site of excellence, constituting yet another test of Singapore’s knack for reinvention.