By Meng Xu

[Picture 1: Hanfu enthusiasts showcase traditional Hanfu during an ACG Expedition in Beijing, 2020]

Hanfu (汉服), or the clothing of the Han people, has become a popular topic in China over the past few years, attracting attention both domestically and internationally. It has been identified and harnessed by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) as an important element of national identity. According to Chinese scholar Tang Min, Hanfu “has aesthetic identity, ethnic identity, and national identity attached to it.”(1)

This blog article argues that the Hanfu revival movement promotes a cultural nationalist identity and is integrated into the mainstream nationalist discourse of multi-ethnic solidarity through CCP’s discourses.

The Revival of Hanfu:

Hanfu was once uncommon in Chinese society but experienced a ‘revival’ driven by various factors. First, as the largest ethnic group in China, Han people lacked a distinctive national costume that could serve as a symbol of identity and belonging for a long time.(2) Although qipao and tangzhuang are often regarded as symbols of Han Chinese clothing, they are criticised for not representing authentic Han styles, as they are adapted from the Manchu clothing of the Qing Dynasty. As a result, some people turned their attention to ‘authentic’ Han-style costumes from earlier dynasties, such as those of the Qin and Han eras.

Moreover, while Han people lacked a distinct national costume for a long time, the recent popularity of historical dramas and the rise of Hanfu e-commerce brought Hanfu back into the public eye,

allowing more people to learn about and appreciate Hanfu.(3) Also, with the development of social media, Hanfu enthusiasts can connect online to share their experiences and gain recognition, encouraging them to post more Hanfu-related content. Under these influences, a Hanfu revival movement came into shape.

[Picture 2: Supporters of the Hanfu revival movement do traditional dances]

Hanfu as National Identity:

Since 2014, ‘cultural confidence’ has been emphasised by the CCP as a key force for inheriting and developing traditional Chinese culture.(4) The Hanfu revival, which reconnects the Han people with their traditional culture, deeply aligns with this trend. As Hutchinson argues, cultural nationalism not only occurs in the early stages of nation-state formation, but it may also be revived again in nation-states with rich histories.(5) As a representation of traditional Chinese customs, Hanfu represents not only a return to ancient culture but also a part of modern Chinese identity, reflecting Han ethnic identity within the broader framework of national culture. Just as Li and Yu note, “Through the restoration of Hanfu and other initiatives, it promotes cultural heritage and contributes to the revitalisation of Chinese culture.”(6) Therefore, Hanfu reinforces awareness of historical traditions, fostering a sense of national community and strengthening ethnic identity, reflecting the cultural nationalism.

The revival of Hanfu also responds to the trans-generational ‘stickiness’ of the culture of nations that Smith describes——national cultures are largely formed through the process of reinterpreting and rediscovering historical memories.(7) Due to the CCP’s emphasis on multiethnic equality, which may have unintentionally diminished the visibility of Han culture, many young Han people began to reconnect with Han culture through rediscovering historical traditions. Therefore, Hanfu, as a historical culture, is reinterpreted as a modern national culture and given meaning to become a symbol of modern Chinese identity.

However, the rise of Hanfu is, to a certain extent, a response to ethnic nationalism. As the Chinese scholar Wang Jun puts it, “The Hanfu movement (is)…a cultural trend based on ‘ethnic’ identity that has been gradually formed both inside and outside the network.”(8) The ‘Han’ aspect of Hanfu may potentially emphasise a ‘Han-centrism’ and promote inter-ethnic divisions.

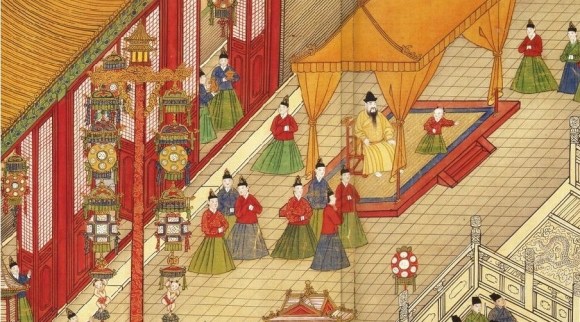

[Picture 2: Palace women are depicted wearing Mamianqun in paintings from China’s Ming Dynasty (1368-1644).]

CCP Leads The Hanfu Discourse:

With the spread of Hanfu culture, the Communist Youth League of China organised the first ‘Chinese Huafu Day’ in April 2018, which attracted significant attention and has continued to grow in prominence. By 2024, the event had evolved from a single memorial day into a week-long celebration, further amplifying its influence. With the growing influence of Hanfu, the CCP recognised Hanfu’s potential ethnic nationalist tendencies and harnessed them into the mainstream discourse of multiethnic unity.

For example, the CCP’s decision to name the festival ‘Huafu’ (meaning Chinese clothing or beautiful clothing) rather than ‘Hanfu’ (directly referring to Han ethnic clothing) reflects a strategic compromise, aligning the festival with the CCP’s narrative of multiethnic unity. Indeed, in addition to Hanfu, the event showcases costumes from China’s various ethnic minorities. This demonstrates how the CCP has integrated the aspirations of Hanfu enthusiasts into its broader ideological framework, constructing a narrative of ‘multiethnic unity and equality’ while diminishing the Han-centric identity associated with Hanfu.(9) Through such endeavours, the CCP intends to strengthen the sense of belonging of each ethnic group to the collective concept of the ‘Chinese nation’, avoiding any possible sense of ethnic division while strengthening the legitimacy of the political party, which will also contribute to the creation of a positive image of multi-ethnic harmony in the international community.

Author Disclaimer: All Chinese sources have been translated by the author.

Image Sources:

· Picture 1: “People Wearing Hanfu at IDO32” by N509FZ, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

· Picture 2: “Supporters of the Hanfu Revival Movement Do Traditional Dances” by N509FZ, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

· Picture 3: “Ming Emperor Xianzong Enjoying the Lantern Festival (Ming Dynasty)” by Imperial Ming Court, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Bibliography:

1. Tang, Min. 2022. “Hanfu as ‘the Power of Identity’—The Production of Identity and Mainstream Integration of Cultural Nationalism in the New Media Environment.” Cultural Studies 2022(7): 93.

2. Ai, Xiumei. 2016. “The Visual Feast of the E-Commerce Era—On the Retro Trend in Urban Clothing Aesthetics Today.” Cultural Studies 2016(2).

3. Zhou, Xing. 2008. “New Tang Suit, Hanfu, and the Hanfu Movement—New Trends in ‘National Clothing’ in Early 21st Century China.” Open Times 2008(3).

4. Chen, Jinlong. 2024. “The Generation, Connotation, and Value of Cultural Confidence.” [Rixiang China]. China Social Science Network—Chinese Social Science Daily, February 6, 2024. https://www.cssn.cn/skgz/bwyc/202402/t20240205_5732439.shtml.

5. Hutchinson, John. 2013. “Cultural Nationalism.” In The Oxford Handbook of the History of Nationalism, edited by John Breuilly. Online edn, Oxford Academic. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199209194.013.0005. Accessed February 24, 2025.

6. Li, Jinzhen, and Shuting Yu. 2017. “On Ethnic Cultural Identity and the Revival of Hanfu.” Heritage 2017(1).

7. Woods, Eric Taylor. 2015. “Cultural Nationalism.” The State of Nationalism. Accessed February 24, 2025. https://stateofnationalism.eu/article/cultural-nationalism/#article.

8. Wang, Jun. 2016. “The ‘Hanfu Movement’ in Cyberspace: Ethnic Identity and Its Limits.” In The Process and Practice of Contemporary Hanfu Cultural Activities, edited by Xiaoyan Liu, 102. Beijing: Intellectual Property Publishing House.

9. Tang, Min. 2022. “Hanfu as ‘the Power of Identity’—The Production of Identity and Mainstream Integration of Cultural Nationalism in the New Media Environment.” Cultural Studies 2022(7): 93.