By Hamza Yousif

Few artists in modern Arab history blurred the lines between culture and politics as seamlessly as Umm Kulthum. Known as Kawkab al-Sharq (the Star of the East), she was more than a singer. Her voice transcended borders, generations, and ideologies. At her peak, she was not just Egypt’s most celebrated artist but a pillar of Arab political and cultural identity. Her music was a vessel for collective emotion, a shared experience that connected people from Cairo to Damascus, Baghdad to Rabat.

Born in 1898 in the village of Tamay al-Zahayra, her rise mirrored Egypt’s own transformation. Raised in a religious household, she first learned tajwīd, the art of Quranic recitation, which shaped her precision and emotional depth (1). Moving to Cairo in the 1920s, she mastered maqāmāt (the melodic modes of Arabic music) and quickly became known for her ability to evoke tarab, the state of musical ecstasy that defined Arabic song (2). She rarely sang a line the same way twice, stretching melodies, improvising, and drawing out words until sound and meaning became inseparable (3).

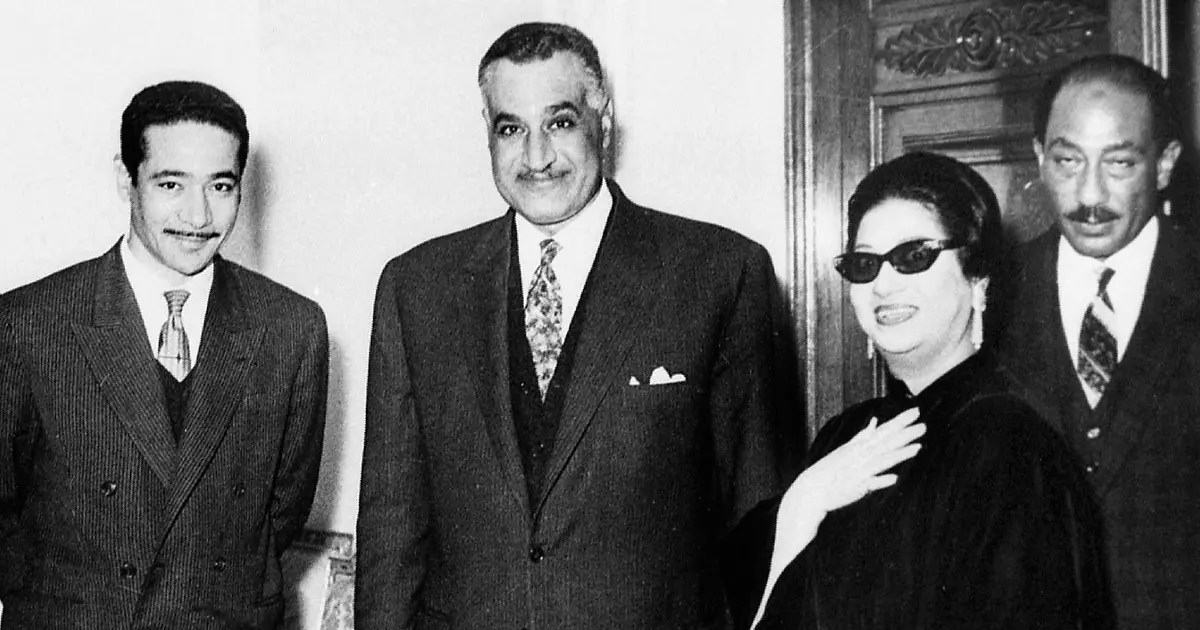

By the 1950s, she was more than an entertainer. Her collaborations with poets like Ahmad Rami and composers like Mohamed Abdel Wahab turned her songs into national epics, but it was her devotion to Gamal Abdel Nasser that cemented her as the voice of Arab nationalism (1). She admired him deeply, seeing in him the embodiment of Egyptian strength and dignity (2). When Egyptian soldiers were besieged in Faluja during the 1948 war, she led efforts to send morale-boosting messages to the trapped troops (4). Among them was a young officer named Gamal Abdel Nasser. When he later rose to power, she became his staunchest supporter.

Her music carried the weight of his vision. More effective than propaganda, her songs became the unofficial anthems of Pan-Arabism. Songs like Wallāhi Zamān (“By God, It’s Been a Long Time”) and Yā Silāḥi (“O My Weapon”) echoed through radios across the region, reinforcing Nasser’s calls for unity (1). When she sang classical qasā’id (classical Arabic poetry set to music), she breathed new life into poetry that had long expressed the Arab world’s deepest emotions. Al-Atlal (“The Ruins”), originally a poem of lost love, came to symbolize the grief of the 1967 defeat, its sorrow mirroring the disillusionment of an entire generation (1). Her kamis al-khamis (First Thursday) concerts became sacred moments. Streets emptied, cafés filled, and for hours, millions sat in silence, consumed by her voice. She understood the weight of her influence and wielded it with precision.

When the Naksa (“The Setback”) of 1967 devastated the Arab world, she did not retreat into mourning. Instead, she acted. Embarking on a fundraising tour across the Arab world, she raised over two million dollars for Egypt’s military (3). In Iraq, Morocco, and Lebanon, her concerts were declarations of resilience. A newspaper at the time remarked, “Umm Kulthum sang of love and collected 70 thousand Egyptian pounds for war” (4).

Her music spoke to the struggles of her people. “Not through hope will the prize be obtained. The world must be taken through struggle” (3). The lyrics had always carried meaning, but in the wake of defeat, they felt sharper. They captured the reality of a people whose dreams of unity had been fractured but whose spirit remained unbroken. Even love songs transformed. When she sang Ba‘īd ‘Annak (“Far From You”), was it about lost love, or the fading hope of Arab unity?

When she passed away in 1975, four million mourners filled the streets of Cairo. It was not just the loss of a singer but the end of an era. Yet her presence never faded. Her voice still echoes through Arab homes, sampled by contemporary artists, and carried in the cultural memory of a region searching for unity (5).

Umm Kulthum Café on Rasheed Street, Baghdad, 2019. (6)

She once sang, “I live for my art, I live for my love.” In doing so, she lived for her people (2)

Bibliography:

(1) Bortolazzi, Omar. “The Sons of the Revolution: Umm Kulthum, Abdel Halim Hafez, and the Nasserist Regime Between Artistic Agency, Propaganda, and Nationalism.” In The Political Impact of African Military Leaders: Soldiers as Intellectuals, Nationalists, Pan-Africanists, and Statesmen, pp. 293-315. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2023.

(2) Danielson, Virginia. The Voice of Egypt: Umm Kulthum, Arabic Song, and Egyptian Society in the Twentieth Century. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008.

(3) Goldman, Michal, director. Umm Kulthum: A Voice Like Egypt. Written by Virginia Danielson. Rashed Media, 1996. YouTube video, 1:07:35. Posted by Al Jazeera English, September 24, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uLfONsv8BEI.

(4) “Interview with Umm Kulthum at the Hôtel Ritz, Paris, November 1967.” Video recording, 9:14. Filmed in 1967. Posted July 17, 2009. Accessed January 11, 2025.

(5) Zakaria, Rafia. “‘She Exists Out of Time’: Umm Kulthum, Arab Music’s Eternal Star.” The Guardian, February 28, 2020.

(6) The Arab Weekly, “Baghdad’s Rasheed Street in the Shadow of Its Past,” The Arab Weekly, October 29, 2017, https://thearabweekly.com/baghdads-rasheed-street- shadow-its-past.