By Jing Kai Lee and Ashley Tan

Figure 1: A side-by-side comparison of posters from the Speak Good English Movement and the satirical Speak Good Singlish Movement. (Source: Speak Good English Movement & thekopi.co)

Singlish, a colloquial language widely spoken in Singapore, has become a key component of the Singaporean identity for a significant number of Singaporeans today. As a local variety of English, Singlish was formed through a mixture of English and local languages (Malay, Tamil, Mandarin, and other Southern Chinese dialects, especially Hokkien). Today, its increasingly contested place within the Singaporean identity has even manifested in calls for a Singlish test for aspiring citizens, in place of its official working language, English.

Yet, the ongoing debate about Singlish’s role today reflects a shift in attitudes from when it was largely seen as distinct from Singapore’s national identity. The story of Singlish can therefore be seen as a movement along a continuum from predominantly materialist nationalism to a blend of materialist and language-based nationalism. Underlying this shift is the nation’s growing agency in defining its own nationalism, beyond the constraints of global forces.

Singlish and Early Singaporean Nationalism

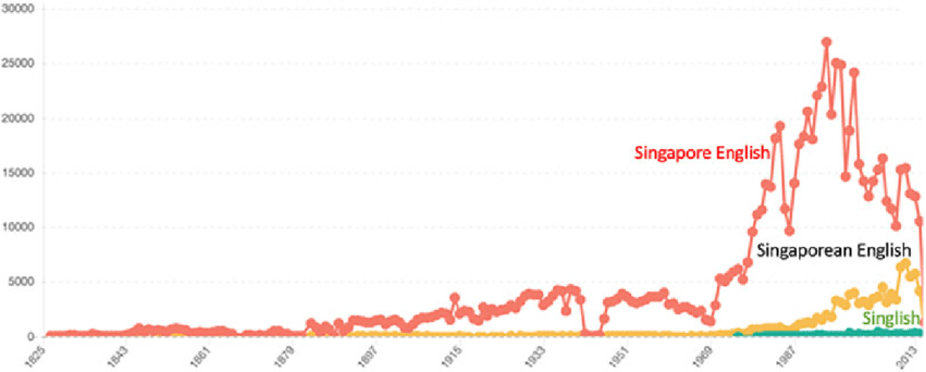

Figure 2: Appearances of terms in local newspapers. (Source: The curious case of nomenclatures: Singapore English, Singlish, and Singaporean English & eresources.nlb.gov.sg)

Singlish has its roots as early as 1825, around the time when Singapore was first established as a British trading post and was welcoming large waves of economic migrants. It was, however, first recognised as a phenomenon only in 1975, ten years after Singapore’s independence. Initially, though, Singlish was not featured prominently within the national political discourse. This changed in 1999 when then-Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong (PM Goh), in his National Day Rally Speech, famously highlighted Phua Chu Kang, an iconic character in a popular Singaporean sitcom, as a character who spoke only Singlish. PM Goh, then, pointed out the advantage that English, rather than Singlish, gave Singaporeans in communicating globally. This stance was further institutionalised in 2000 when the Speak Good English Movement was launched which sought to reduce Singlish’s usage in favour of English through public awareness campaigns. PM Goh argued at its launch that poor English risked causing Singaporeans to be perceived as less intelligent and capable. He warned that poor English would harm investor confidence and undermine Singapore’s ambitions to become a first-world economy.

Given PM Goh’s framing then, we might infer that the primary function of language, as conceived in early 2000s Singapore, was to be intelligible. This can be contrasted with alternative functions of language, such as being a marker of identity or a means of emotional expression/self-expression. Therefore, given that the value of language to the nation was appraised based on its impact on economic competitiveness rather than on its historical resonance or aesthetic qualities, this suggests a stronger emphasis on materialist nationalism in the early 2000s.[i]

Underlying this is the dimension of the nation’s agency to shape Singapore’s national identity. The global business community is identified as the primary target audience for this language, implicitly contrasting with approaches focused on intelligibility at national or sub-community levels. In early 2000s Singapore, global business validation seems therefore to have taken a relatively large place in relation to more internal sources of national validation.

Singlish and Singaporean Nationalism Today

Fast forward to today, the status of Singlish has undergone marked shifts.

Singlish is now increasingly contested as a legitimate language in its own right. Singaporean writer Gwee Li Suiunderscores the richness of Singlish. He argues that Singlish is more than a pidgin language that substitutes English words for Malay or Hokkien; it is one with its own syntax. This linguistic discourse matters because it is a contestation between the nation and the global marketplace about the agency to define normative standards of validation. The persistence of Singlish’s use, and the warming attitude towards it, signals the increasing agency for the nation to shape its own nationalism today.

There is also an emerging view that Singlish can coexist with English. Today, Singlish and English are seen to exist complementarily rather than in opposition to one another; Singlish is understood to be the language of community, while English is acknowledged as the language of professional business. The emphasis has accordingly shifted towards code-switching between the two languages instead of learning one and unlearning the other.

Reflections

Singapore’s nationalism has shifted over the years from a predominantly materialist nationalism towards one that embraces more language-based nationalism. It is also increasingly defined by the nation,rather than being constrained by global forces. Perhaps this might be seen as part of a broader structural shift; where materialist nationalism once had greater aspirational resonance at a time of lower incomes, rising economic standards today have since allowed for more post-materialist national aspirations.

[i] Pablo de Orellana and Nicholas Michelsen, eds., Global Nationalism: Ideas, Movements and Dynamics in the Twenty-First Century (London: World Scientific, 2023), 24.