Written by Andrey Miroshnikov

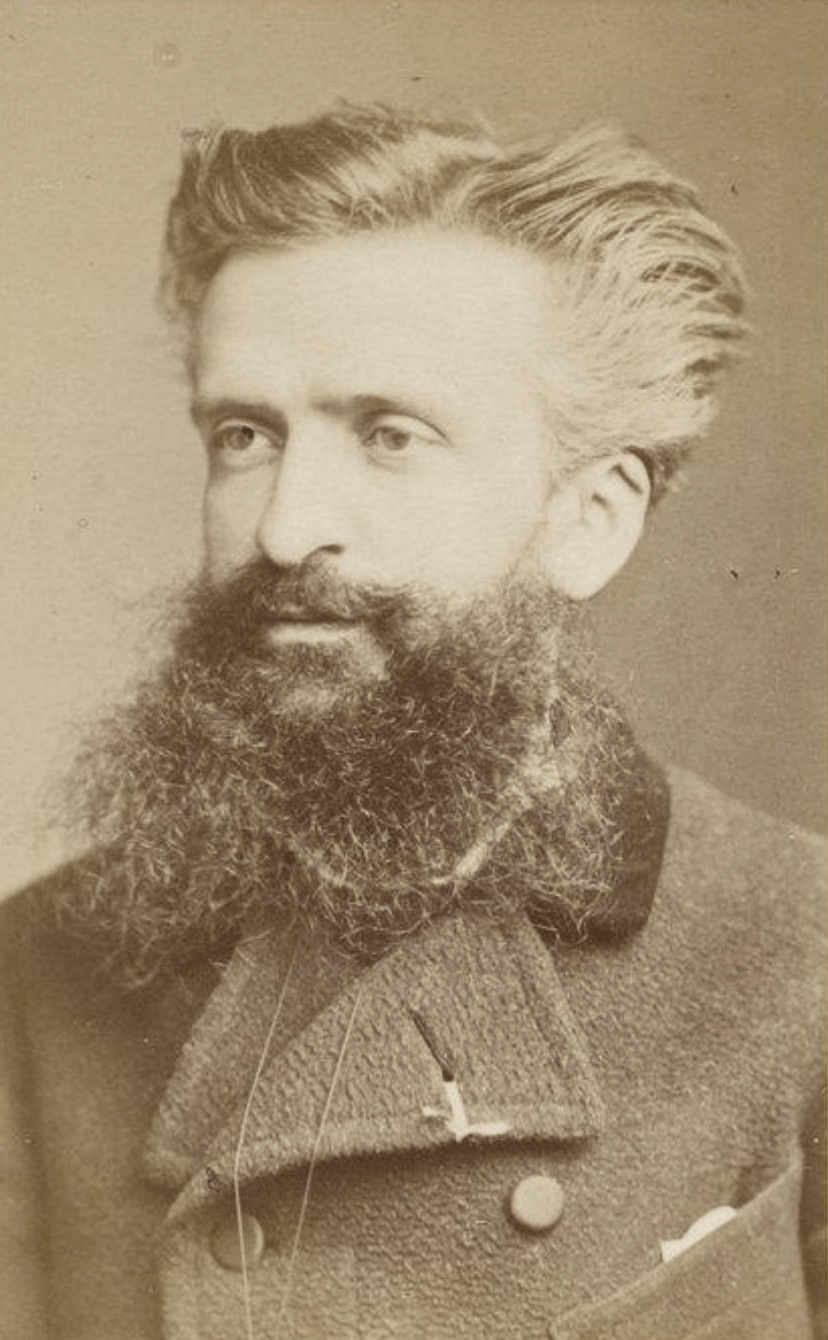

First published in 1895, Gustave Le Bon’s The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind has assumed an enviable place in the history of influential literary works as much for the ideas it popularised as for the fame of those who supposedly used them. While the Frenchman’s work is said to have informed Sigmund Freud’s and Carl Jung’s thinking on group psychology, it is also imputed with moulding the oratory of Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler. (Reicher, 1996, p.538) The stubborn longevity of Le Bon’s magnum opus bewilders ever more as its originality and scientific validity are called into question. If the text is merely an instance of unabashed plagiarism and undue simplification of the preceding works of sociologists like Scipio Sighele and Gabriel Tarde, why should it attract our attention? (McClelland, 2010, p.152-153) It is a view of some, notably Susanna Barrows (1981, p.196), that the contribution of Le Bon’s labour goes beyond the field of crowd psychology and as far as the shaping of the 20th century right-wing politics. Although the claim of the Frenchman’s central role in laying the groundwork for the future political discourse appears tenuous at best, a brief look at his work reveals why such assertions are less absurd than they may seem at first.

Le Bon’s preoccupation with inherited personality traits and race driven psychological differences is evident throughout the book. But apart from an occasional ascription of some activity to a particular racial group, which conveniently corresponds to a nation, the text is surprisingly reticent about constructing a hierarchy of European races. The author’s sympathy for the English ‘race’ notwithstanding, little is said of his attitude towards ‘the love of dancing’ and the fondness for ‘music’ supposedly running in the blood of the Spanish and the German ‘race’. (Le Bon, 2001, p.82) However, in the best traditions of racial discourse, Le Bon does not oblige the reader to wait long for the other shoe to drop. And when it does, we discover that most of the non-European races are implicitly confined to the category of ‘savages’. (Le Bon, 2001, p.10) Perhaps out of pity for the lonely brute, the same disagreeable badge of ‘inferior forms of evolution’ is pinned on women and children. (Le Bon, 2001, p.10.) Herein lies the apparently recurrent trope of racial politics that begins with the initially innocuous claim of racially determined inclinations (the love of dancing or music) and has a chance of later morphing into an implied or explicit assertion of innate superiority. But as much as race informs Le Bon’s discussion of crowd psychology, it is mostly used as the means for understanding the changes in the individual’s behaviour ascribed to them becoming part of the crowd.

Of all the social categories featured in Le Bon’s text, the crowd elicits most of the author’s contempt. It is imputed with stripping the individual of their conscious personality and dramatically altering their standard behaviour. (Le Bon, 2001, p.1-2, p.4) Both are seen to lead to the formation of the ‘collective mind’ which is impregnable to critical judgement and instead driven by emotions and the ‘unconscious’ traits of the race. (Le Bon, 2001, p.4, p.34, p.5) Based on the characterisations provided so far, the reader might reasonably imagine how, according to Le Bon, a gathering of Spaniards or Germans inevitably descends into a fiesta or a class on musical composition by the virtue of the races’ unconscious predispositions, which are normally repressed by the individual but unleashed by their presence in the crowd. The functionality of a multiracial crowd is dismissed out of hand with a reference to ‘the wide divergencies’ between the ‘inherited mental constitution[s]’ of its members. (Le Bon, 2001, p.102) To phrase it differently, the Spanish-German crowd cannot but be discordant in view of the racial differences in the unconscious of its members. Needless to say, the case of a German with an immediate Spanish heritage is not raised out of concern for the theory’s coherence. What is brought up, however, is the violence and obedience of the crowd. (Le Bon, 2001, p.9, p.75) Fortunately for the reader – who has, no doubt, been expected to develop a loathing not only for the crowd but also for the thousandth reminder of just how evil the author perceives it to be – Le Bon proceeds to share the ‘well-known’ methods for mastering the crowd. (Le Bon, 2001, p.23) This constitutes the more practical and insightful section of the book – assuming, of course, no prior knowledge of these ‘well-known’ techniques on the reader’s part.

The formula for swaying the crowd approved by Le Bon involves at least three elements: affirmation, repetition and contagion. (Le Bon, 2001, p.23) Given the crowd’s ‘suggestibility’, the public speaker is advised to ‘make an abusive use of violent affirmations’, intended to impassion the audience. (Le Bon, 2001, p.7, p.23) Apart from rational reasoning, no rhetorical device appears off the table when

dealing with the crowd. (Le Bon, 2001, p.23) Once the affirmation most resonant with the audience is found, it is to be hammered into the bovine mind of the crowd through merciless repetition until it becomes deeply entrenched and spreads in the midst of the public as a contagion. (Le Bon, 2001, p.78) To ward off any potential or real voice of dissent, the speaker is encouraged to ‘destroy’ their reputation with the help of the same triplet of demagogic tools. (Le Bon, 2001, p.115-116)

Now, for those of us who are not above watching Trump rallies, Le Bon’s blueprint for winning over the crowd and piquant mud-slinging sounds eerily familiar. Speaking at the Conservative Political Association Conference (C.P.A.C.), the 45th U.S. President studiously complied with all of Le Bon’s recommendations. Eleven minutes and fifty-odd seconds into the speech, he affirmed the self-promulgated dictum of America’s likely collapse in case ‘crooked Joe Biden and his thugs win in 2024’. (C-SPAN, 2024) The remark’s gist was subsequently repeated at least seven times, allowing for such nuanced characterisations of the incumbent President as ‘the crookedest’, ‘incompetent’ and ‘not strong on aptitude’. (C-SPAN, 2024) Whatever the present public perception of President Biden might be, it does not come across as immensely complimentary about his tenure. The extent to which this contagious attitude is the outcome of Trump’s assiduous efforts is certainly not negligible. This pattern of affirmation, repetition and contagion could be discerned in most of the Republican’s talking points. Does it therefore signify the continued relevance of Le Bon’s text and turn the Frenchman into an architect of right-wing politics?

The Crowd does not boast a great many epiphanic passages or literary merits. Yet, neither of which might have been within the reach of this article’s author for the possible reason of him ‘not [being] strong on aptitude’, let alone having scant knowledge of French – the language in which the book was originally published. This caveat aside, Le Bon’s work is not entirely devoid of stimulating reflections. His description of the kind of individual who would be best suited to mastering the art of crowd manipulation is not off the point. The ‘morbidly nervous, excitable, half-deranged persons who are bordering on madness’ and have an indomitable faith in their convictions do, indeed, seem to make historic orators. (Le Bon, 2001, p.72) No less engaging is a proposition explaining the crowd’s proclivity to choose as their leader the individual who is not from their ranks; the plain lack of ‘prestige’ of those who are appears sufficient to hamper their elevation. (Le Bon, 2001, p.115) A diligent reader might uncover other intriguing remarks. But even the reader who is reluctant to peruse the text cannot be blind to the remarkable pertinence and incisiveness of some of its observations. In fact, they are echoed by a no less perceptive observer than the late Martin Amis himself. In an essay depicting the experience of being at a Trump rally, the British novelist notes how those in attendance ‘had surrendered their individuality to the crowd’ and collectively transmogrified into a ‘colossal beast’ which performed chants, boos and cheers ‘at the direction of its tamer’. (Amis, 2018, p.358) Wading through The Crowd, one invariably thinks of other instances when Le Bon’s portrayal of crowd behaviour corresponds with the impressions of others. What also springs to mind are examples of world figures whose rhetoric adhered so closely to the tenets of crowd manipulation described by the Frenchman at the close of the 19th century. This in itself might suffice in explaining the enduring legacy of Le Bon’s The Crowd.

Bibliography

- Amis, M. (2018). The rub of time: Bellow, Nabokov, Hitchens, Travolta, Trump and

other pieces, 1994-2016. London: Vintage. - Barrows, S. (1981). Distorting Mirrors. Yale: Yale University Press.

- C-SPAN (2024). Campaign 2024: Former President Trump Speaks at CPAC | C-

SPAN.org. [online] http://www.c-span.org. Available at: https://www.c-

span.org/video/?533737-1/president-trump-speaks-cpac [Accessed 28 Feb. 2024]. - Le Bon, G. (2001). The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind. Mineola, NY:

Dover Publications. - McClelland, J.S. (2010). The Crowd and the Mob (Routledge Revivals).

Routledge. - Reicher, S. (1996). ‘The Crowd Century: Reconciling Practical Success with

Theoretical Failure.’ British Journal of Social Psychology, 35, 535-553.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8309.1996.tb01113.x

Picture Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gustave_Le_Bon