Written by Charles Khalaf

“That of the ancestors is the most legitimate, for the ancestors have made us what we are. A heroic past, great men, glory, this is the social capital upon which one bases a national idea.” –Ernest Renan

“Lebanon is the preeminent crossroads where varied civilizations drop in on one another, and where bevies of beliefs, languages, and cultural rituals salute each other in solemn veneration” -Michel Chiha

Amist the queue for passport control on the northern Lebanese Syrian border stood Bashir Khalaf, a Maronite from Mount Lebanon. Surprisingly, Mr. Khalaf picked the counter where a clear sign says, “non-Arabs”. After approaching the counter for the paperwork, the Syrian border officer was surprised to see the man carrying a Lebanese passport, demanding an explanation. In a moment that captured the attention of everyone in the queue, Bashir stood tall and replied with unwavering pride, “I am not Arab; I am Phoenician Lebanese”. A look of horror appeared on the Syrian officer’s face as he replied, “I think you’re neither; you are a Hmar (donkey)” and with disdain, he tossed Mr. Khalaf’s passport into the midst of the queue reserved for Arab travelers.

This seemingly trivial encounter at a border crossing unveils a clear identity crisis that has permeated Lebanese society for decades. It clearly shows how a man sees the nation through the lens of his own perceived identity against other opposing ones. However, the role of identity does not stop here. It is a serious tool that has been used by nationalist discourses to serve much bigger purposes, sometimes being problematic. A closer look at Phoenicianism in Lebanon through a historical interpretation based on identity exposes a strong mechanism that not only overshadows the historical inaccuracies of a nation, but also leads it to a violent path.

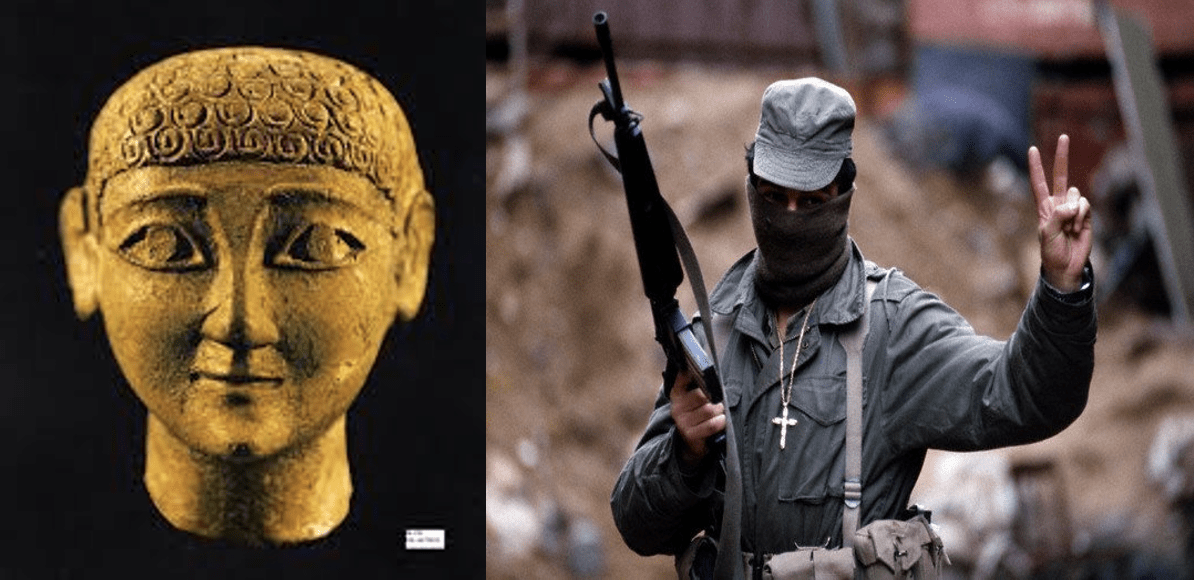

The term Phoenician is of Greek origin found for the first time in Greek texts dating as early as the 9th century BC, aimed to identify the stretch on the Syrian coast between Latakia and Acre. The beginning of the Phoenician era is marked by archaeologists and historians around 12 000 BC, between the end of the bronze age and the beginning of the Early Iron age (Kaufman, 2014). It was on the coast of present-day Lebanon that the three greatest Phoenician city-states flourished: Byblos, Sidon and Tyre. However, it is important to note that these Canaanite/Phoenicians identified themselves according to their city-state (Tyrians, Sidonites…) and not their Phoenicianism having never acquired political unity of any sort (Kaufman,2014).

The ancient inhabitants of the Lebanese coast did not refer to themselves as Phoenicians, but as Canaanites, referring to merchants from the land on Can‘an in Biblical Hebrew (Kaufman,2014). This suggests that the name of this civilization may have derived from their most popular profession, commerce.

In their times, the Phoenicians have been great trading people who had established colonies all around the Mediterranean world, with Carthage as their most important one in present day Tunisia. They went as a far founding towns that are important trading centers to this day such as Barcelona in Spain and Marseille in the south of France (Salibi, 1988). The Ancient Greeks took the alphabet of the Phoenicians that was refined in the form of numbers and letters to become the bases of the Greek Hellenistic alphabet, which is the direct ancestor of the Latin alphabet of Western Europe (Salibi,1988). This is considered as the civilization’s greatest export and contribution to the intellectual development of humankind. After being conquered by the Persians, Alexander the great and then the Romans, the Phoenicians cities of present-day Lebanon maintained their commercial supremacy forming an important center of the Hellenistic civilization. This Glorious story put together provided a distinguished pre-Arab Antiquity for Lebanon, upon which a seemingly attractive Phoenicianist theory of Lebanese history could be constructed.

In the 7th century AD came the Arab conquest of the Levant, along with the Phoenician cities that became Arabized and lost their ancient particularity. However, it allegedly reincarnated itself again in a discreet and elusive way. This time, the reassertion of Phoenicianism came in late 19th century Mount Lebanon. It would argue that resistance to Arabisation proved infeasible in the ancient Phoenician cultural hubs, and the reaffirmation of Lebanon’s Phoenician identity found refuge and endured primarily in the mountainous area until the modern era when it remerged politically in the form of Greater Lebanon (Cobban, 1985). Hence, the modern Lebanese nationality was nothing more than the ‘direct’ resurrected descendant of the ancient Phoenician ‘nationality’.

No one could deny that the Phoenicians had once lived on the same land the Lebanese live in today. But how is this 19th century revivalism in the mountain connected to the ancient inhabitant of coastal Lebanon? A historical genealogy would show that there is no single historical link or linear continuation between the Phoenicians and Lebanese, least of all inhabitants of Mount Lebanon. Since the 19th century, Lebanon undoubtably belonged in the intellectual and cultural realm of the Arab world, where its inhabitants were none other than fellow Arabs. Earlier on, the inhabitants of Mount Lebanon were usually illiterate peasants who had made no valid contribution to human civilization. It wasn’t until the middle decades of the 19th century that people in Lebanon knew about the existence of the Phoenicians, beside the graduates of the Maronite college in Rome who had bothered to read the Greek classics (Salibi,1988).

In this Christian Lebanese Myth, the people of Lebanon were seen as Phoenicians who were simply not Arabs, having inherited from their ancestors not only their mercantile character but, specifically, their intellectual ‘Eminence’. Even though the Phoenicians used the alphabet, there is no archaeological evidence of any literature left by them aside from an inscription in Phoenician alphabet left on the tomb of a king of Byblos that includes only curses against anyone who disturbed his sarcophagus (Kaufman, 2014). They excelled in commerce and seafaring but in little else.

Identity itself is not the problem here, but the way it is being used in this constructed theory of state by nationalists to serve a hierarchical purpose.

Aside from justifying the existence of Greater Lebanon independent from its Arab identity in 1920, Phoenician identity was aimed at giving its advocators, mainly the Maronites eminence over their compatriots. The creation of Greater Lebanon in 1920, which came as an extension to “Christian” Mount Lebanon, was labelled Phoenician by proud Christians and angry Muslims who found themselves part of a state calming to be different than their cultural Arab surrounding. The Maronites already considered themselves as a “rose among the thorns” in the region, as described by Pope Leo X in 1510 (Salibi, 1988). A normative superiority came alongside the extension of the land to form greater Lebanon around a special confessional hierarchy where Christians acquired paramount control in a state that they were merely the majority in. Ironically enough, even if we were to disregard the historical inaccuracy of the Phoenicianist theory of state, if anyone were to assert descendance from the ancient Phoenicians, it would more likely be the residents of the coastal cities who are generally Muslims identifying as Arabs, rather than the Maronites of Mount Lebanon.

In 1920, a Lebanese state might have been created but a nation on the basis of Phoenicia resurrected was far from emerging. At that time, Phoenicianism became associated only with Christians of Lebanon and would later be known as Lebanism (Cobban, 1986). One could easily correlate these two theories of state that complement themselves in a primordial manner defining Lebanese national identity separate and ‘eminent’ from its Arab background. However, the other inhabitants of Greater Lebanon, mainly Muslims, did not buy the ideas of Christian Lebanese nationalism and saw national identity through their own, that of Arabism. After Lebanon would gain its independence from French mandate in 1943, the battle of identities would begin with Lebanism and Arabism at the forefront. This struggle would have far-reaching implication on the modern state of Lebanon, turning into a deadly civil war in 1975 that would claim 150 000 lives in a brawl of identities fighting to claim the nation (Rabah, 2020).

Lebanese historiographer Kamal Salibi would argue that the war was waged against different interpretations of Lebanese history, which at one stage or another were linked to certain national aspirations (Salibi, 1988). Yet, what chances of success could the interpretation of history have in a society where not everybody was committed to being rational? Lebanon today is yet to recover from the consequences of the war, where no single identity has prevailed over the other. The fragmentated nation turned into a failed state that disgraces its citizens and the land once inhabited by glorious civilizations.

One cannot deny the important role of Phoenicians in the patrimony of modern Lebanon. They might not be direct ancestors of the Lebanese, but Phoenicianism can be seen as the history of the Land rather than the history of people. In every nation and community, people find certain historical eras more appealing than others. However, the History of Lebanon does not belong to anyone. It is distinguished by its beautiful civilizational diversity and not by clinging to this or that epochs. This diversity is not a historical myth, it is exactly what makes the country special, a global village where the glory of different human civilizations reside. Therefore, the ancient history of Lebanon cannot be claimed as an alternative identity to its natural and real Arab character. Viewing it as so has been restricted to a small group in Lebanon with a hierarchical purpose clearly shown in the article.

In 1975, Bashir Khalaf enlisted in the Lebanese Christian militias to fight for his own version of Lebanon, the one he saw through his Phoenician identity. In one of the fierce street battles of Beirut, he was shot and laid on the ground bleeding on the same soil his beloved “ancestors” once exported the purple colour to the world. Yet the colour exported Bashir that day was no more than his red perished blood, in the name of a certain “Phoenicia resurrected”, one that would remain a myth to this day.

Bibliography:

- Cobban, Helena. The Making of Modern Lebanon (1st ed.) 1986. Routledge, 1986.

- Kaufman, Asher. Reviving Phoenicia : The Search for Identity in Lebanon. London: I. B.Tauris, 2014.

- Makram Rabah. Conflict on Mount Lebanon: The Druze, the Maronites and Collective Memory. Edinburgh University Press, 2020.

- Salibi, Kamal S. (Kamal Suleiman). A House of Many Mansions History of Lebanon Reconsidered. London: I.B. Tauris, 1988.

2 replies on “Phoenicia resurrected: When Ancient Civilizations meets Modern Nationalism”

Very interesting article!

LikeLike

Great article 👍🏻

LikeLike